The best game of the decade: That Dragon, Cancer

That Dragon, Cancer is a window into the soul, probing our collective thoughts and feelings in a way that feels at once real but with sweeping flourishes so as to constantly invigorate.

_ | Contributed photo

That Dragon, Cancer is the best game of the decade.

Part documentation of the short life of cancer victim Joel Green from the perspective of his parents Ryan and Amy — who largely designed and wrote the game — and part abstract reflection of their state of mind as they watch their child slowly die.

It presents a staggeringly tender look at the effect of cancer on those who suffer.

From the propensity to remember those who have passed away to the effect a stranger’s work can have on someone you love, as well as more unifying concepts like the reason we create art and devote ourselves to religion. That Dragon, Cancer dives head-first into exploring so much of what makes humanity grandly beautiful.

It is such an encompassing look at human behaviour, emotion, memory, perception, faith and other essential aspects of our lives that it feels limiting to call this a product available on the Steam store page for $17.

It might even be limiting to call it a work of art.

That Dragon, Cancer is a window into the soul, probing our collective thoughts and feelings in a way that feels at once real but with sweeping flourishes so as to constantly invigorate.

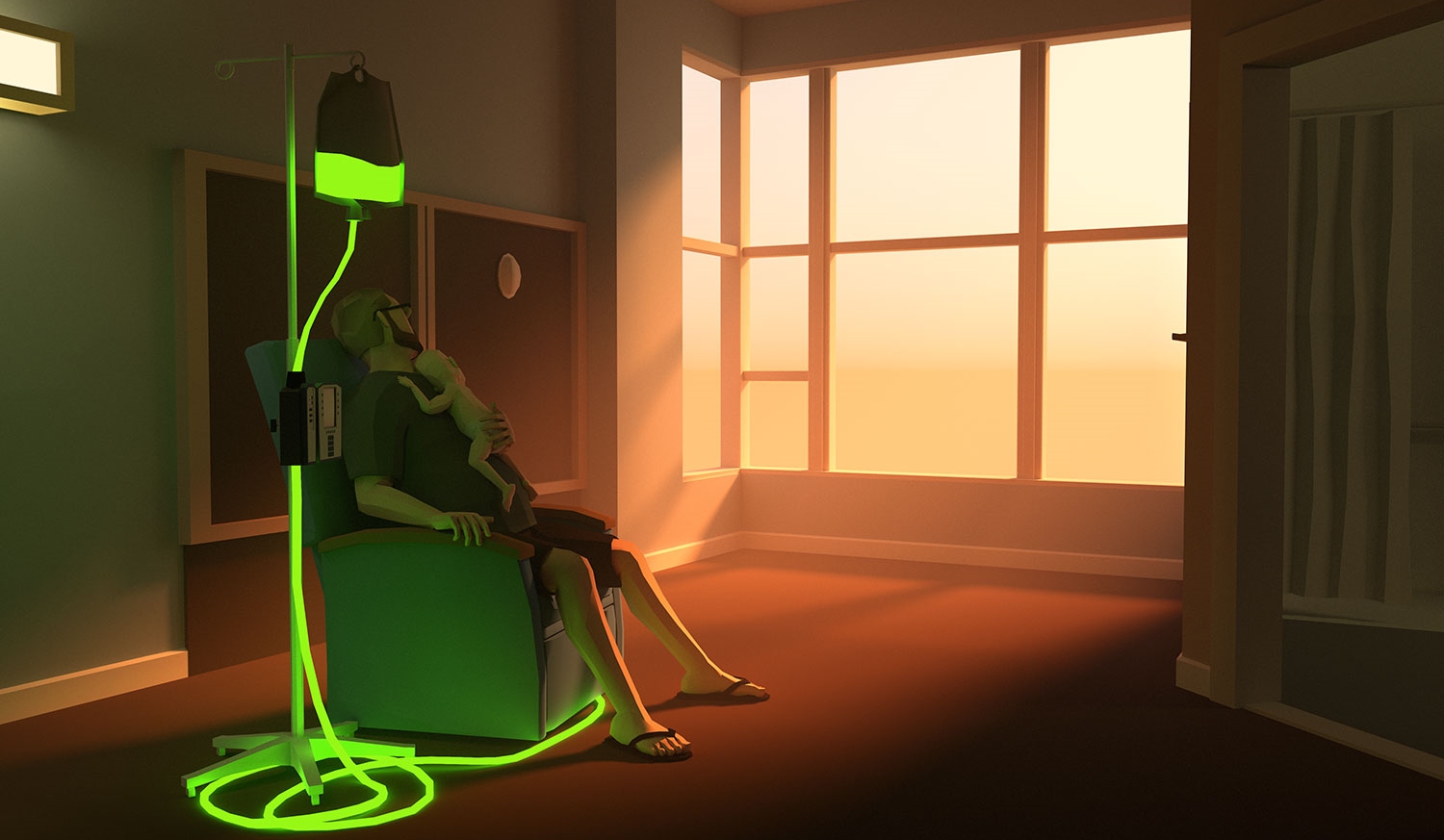

That Dragon, Cancer is not a work of fiction, yet it contains cosmic seas so vast and majestic that inevitable graphic limitations can’t stop them from replicating infinity. Even the real-world environments are lit so elegantly and composed so melodiously — as is the gorgeous music — that it puts multi-million dollar productions to shame and casts a gentle sun onto the mundane staples of our daily lives, like a pond or a hospital. But occasionally that hospital contorts into a wasteland, riddled with pitch-black cancer cells and watched over by that dragon.

The dragon is always there even when you can’t see its shadow. Back in “reality,” Ryan sits in a bedside chair while watching over Joel; powerless to stop the child’s pained and dehydrated howls.

“I know you’re thirsty buddy but you’ll throw it up,” he desperately reminds the both of them, head in his hands. He prays for peace and Joel goes to sleep. “Thank you,” he says, tone hushed so as to not wake his son.

The game jumps between time and point of view, allowing moments like this to be seen from the perspective of his mother, Joel himself and even the doctor who tells Ryan and Amy how long their son has to live. He cries a little. I imagine a lot of pediatric doctors do.

You probably will too. I know I did. Even if you have no hard experience with cancer, the game’s use of the audio from the Greens’ home movie collection blends with community submitted stories and letters from experienced cancer survivors or relatives of victims to tap into the universal human experience.

This isn’t about a family, but about all of us and why we bother to empathize with each other.

We are connected by universal truths, and the way That Dragon, Cancer hones in on this fact makes it larger than any open-world sandbox, grander than any choral score and more detailed than any facial-rendering technology.

The future of games is here, and how overpowering is its arrival.