The Bechdel test: simple guideline with complex connotations

As people who appreciate all kinds of cinema, it may be best for us to look at the Bechdel test as its creator did — as a minor gripe indicating a major problem.

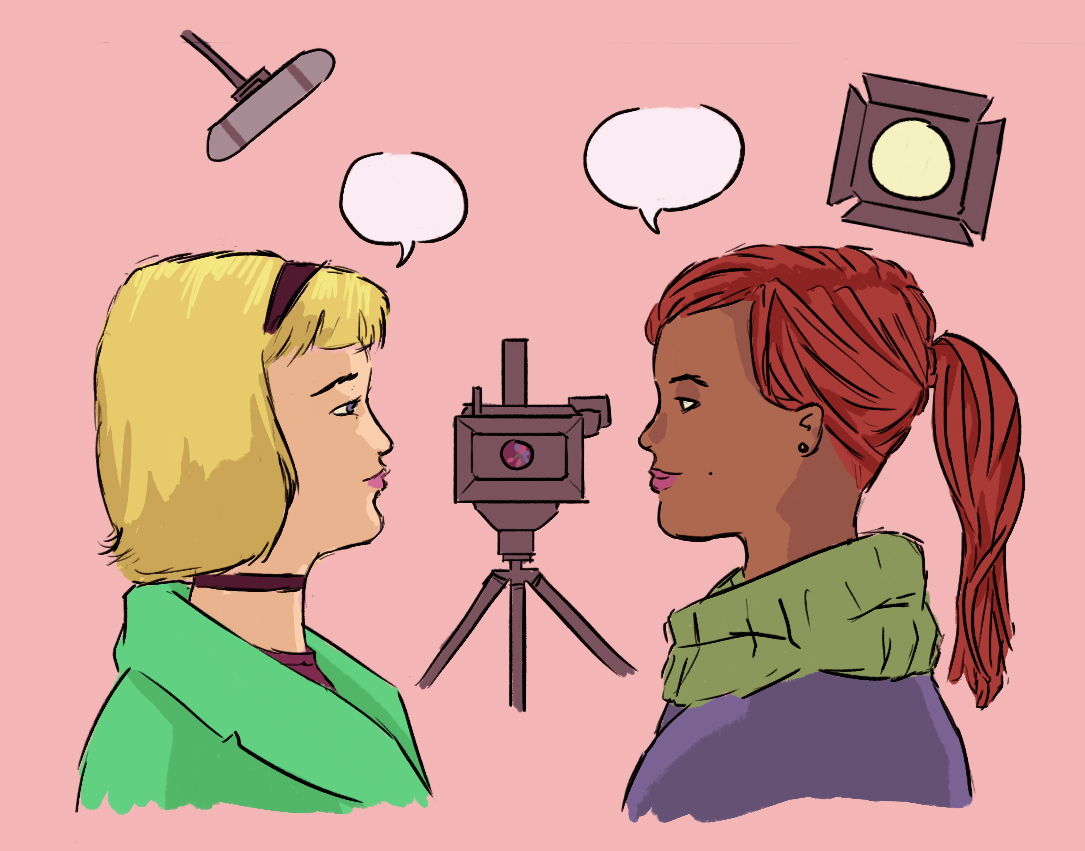

In 1985, Dykes to Watch Out For — a comic created by Allison Bechdel — aired a piece about two unnamed characters discussing going to the movies. One has hesitation about it, though, as she says she has three rules about seeing movies: it must have two women in it, they must talk to each other at some point and it must be about something other than a man. It ends with a short moment of stumped contemplation, then the two walking away from the theatre and deciding to go to her partner’s place instead.

This idea has caught on rather strongly in the world of cinema academia in the last few years, taking on the name of the “Bechdel test.” While some see it as a good component of measuring the influence of female characters on a film’s narrative, others see it as being overly simplistic in terms of looking at said influence and the representation of women in film as a whole.

It’s odd that so many smart, film-inclined people would shape a way of analyzing movies from a throwaway idea of a person with no former background in film or film theory. In the comic, Bechdel was not trying to create a complex way of viewing gender in film, but rather how an ordinary moviegoer – in this case, a homosexual woman – may look at the kind of movies she would want to experience because of the way that she views the world. It’s a basic and simplistic outlook, but one grounded in a genuine and complicated concern — why are women treated as minorities in a medium where they consist of fifty-two per cent of its consumers?

The problem lies in the fact that in Hollywood, women really are minorities. According to Hollywood Reporter, six per cent of directors of major films in 2013 were women, as were ten per cent of screenwriters and seventeen per cent of editors. Because most directors and screenwriters are men, they are primarily going to make films about subjects that interest them, which more often than not will be on topics that interest them as men, such as power-fantasy action movies like Edge of Tomorrow and Pacific Rim. As a result, they are far less likely to pass the test or even have more than one or two tertiary women so as to not seem sexist.

This is unfortunate not just for moviegoers who would like to see more characters they could easily relate to, but also for the industry as a whole because it creates lack of variety in the kind of movies that survive the arduous journey from script to distribution. As a guy it would be great to see more big movies about people who I can’t immediately connect to, as the films can be just as engaging because they tackle subjects that I’m not inherently familiar with. While there are tons of complex reasons as to why that balance hasn’t shifted yet, it’s still unfortunate for moviegoers who want to be challenged.

However, it is unfair for those to use the Bechdel test as a means of judging an individual film’s merits. I called Edge of Tomorrow and Pacific Rim male power-fantasies, but that doesn’t change my opinion that they were both really good. Likewise, Jack and Jill technically passes the criteria of the test, but it’s a widely despised movie regardless of this very mild kudos.

Because of this lack of consistency in what the test itself can or can’t determine, it’s a better barometer of testing the state of equal-representation in Hollywood through the passing and failing of numerous movies rather than a test of how individual films portray gender.

As people who appreciate all kinds of cinema, it may be best for us to look at the Bechdel test as its creator did — as a minor gripe indicating a major problem.