Recovering against all odds

In 2011, Karen Roma didn’t expect to be spending Christmas Eve in McMaster Children’s Hospital in Hamilton, Ont., sitting beside her son’s bed waiting for his blood work to come back from Harvard University.

She didn’t expect to be sitting there, surrounded by her family — which included her other 15-year-old son — waiting to find out if her child had leukemia.

“I was in shock. I couldn’t believe it. How could this be? He basically was a healthy kid. As a mom, you don’t think you’re going to hear that your kid has cancer, right?

“Then maybe I thought it was a mistake, but it wasn’t.”

Nick Roma was only 17 years old and was a high school senior at Saint Paul Catholic High School in Niagara Falls when he was diagnosed with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL).

While most typical cases undergo 25 months of chemotherapy treatment and therapy, Nick was an irregular case. His journey was filled with complications and even his mother said he’s lucky to be alive today. He’s considered a “miracle” by family and friends, and it all began with a tired feeling.

The beginning

Nick had been feeling tired in the beginning of December 2011, but he wasn’t sick often and rarely complained about pain.

But in the coming weeks, things started to change.

“He started getting pain in his jaw, so I took him to the dentist and they told me it was his wisdom teeth. [But] when the dentist cleaned his teeth, [they were] covered in blood,” Karen said. “The dentist said, ‘I think he needs to floss better,’ but it wasn’t that at all.”

The next day at school, Nick was in so much pain that he could barely stand up.

“Kids took pictures of him lying on the ground and thinking he was joking, thinking he wanted to get out of working. They were moving desks from one place to another and he couldn’t do it,” Karen said.

That night, Nick went home and slept for hours. His father, John, noticed something wrong and took him to the walk-in clinic to be checked.

But when the clinic told the Romas to come back in the morning for Nick to do blood work, he fainted.

“I felt very weak, tired and sore,” Nick said. “I had no motivation to do anything at anytime.”

The clinic didn’t have a doctor, so Nick was sent to Greater Niagara General Hospital (GNGH). According to Karen, Nick’s blood work indicated incredibly low numbers. His platelets, which are the blood cells that clot blood and stop bleeding, were at a level of 11, when they are typically between 250 and 400. His hemoglobin, a protein responsible for transporting oxygen in the blood, was at a level of 27, which are typically 150.

“I left work, I rushed to the hospital and he’s all hooked up to IVs and had blood transfusions and was on his third transfusion by the time I go there,” Karen said.

Nick went through immediate blood transfusions at GNGH before being transferred to McMaster on Dec 23. He went through a blood marrow biopsy before having his results sent to Harvard to be evaluated. Christmas Eve, the Romas — and Nick’s girlfriend, Kara Brown — were given the news that Nick was diagnosed with ALL and would have to undergo immediate chemotherapy.

“They wanted to start chemotherapy right away because it was acute and he was very close to dying at that point,” Karen said.

“When he was first diagnosed I didn’t know what to expect,” said Brown, who has stuck with Nick through the entirety of his diagnosis. “The word ‘cancer’ had many things running through my mind.”

Living with Leukemia

Generally, cancer is not very common in children. According to Carol Portwine, a pediatric hematologist oncologist with Hamilton Health Science (HHS) and associate professor with McMaster, only about 14 to 15 people in a 100,000 population are diagnosed with leukemia, a form of cancer that affects the white blood cell count in a person’s body.

Acute leukemia makes up about one third of all cases of cancer in children, and while it’s not very common, it is the most common type of cancer in children.

“Leukemia in a general statement is kind of a chameleon,” Portwine said. “People can present very, very well …. Or, they can present very, very ill …. The presentation is not duplicated in any individuals. It’s really a vast array of how any individual will present with an acute leukemia.”

ALL is more common in children, while the other form of acute leukemia, acute myleoblastic leukemia (AML), is more common in adults. To diagnose leukemia, a blood test is taken and evaluated based on if the leukemia cells are already in the blood stream. However, a bone marrow test must also be done in order to properly observe the cancer.

“The bone marrow is really a factory, where all the baby cells are made,” Portwine said. “So we want to see how the factory is doing because the factory with leukemia is producing a lot of bad cells and a lot of leukemia cells.”

According to Portwine, there are many tests that are done to see what type of leukemia the patient has, if there are any specific genetic changes to the cells and if it could be a more favourable, or “better” prognosis, or a bad prognosis. Treatment with leukemia, and specifically with ALL, is predominantly chemotherapy. Portwine said that it can include radiation depending on the severity, but everyone will receive chemotherapy.

“People often ask if transplant is also part of the treatment and it’s not part of the upfront therapy,” Portwine confirmed. “So we’d never be discussing a transplant except for very exceptional cases when based on certain tests it shows that it’s a very resistant form of ALL. But for the vast majority, it’s chemotherapy, plus or minus radiation.”

In Nick’s case, he received treatment immediately following his diagnosis. Portwine said his treatment — from time of diagnosis — runs for two years and a month. The initial month is an aggressive induction of chemotherapy to get rid of all “apparent evidence” of the disease, and then a normal induction of therapy for the following two years.

Bright times

After a few months of treatment, Nick seemed to be doing well. He was considered an inpatient at McMaster for about six weeks in December before being allowed to live at home. He had to go to Hamilton every Thursday for chemotherapy, and received schooling from home in order to graduate on time, which was the upcoming June. He suffered hair loss from the chemotherapy and other common symptoms, but his cancer was in remission in time for the final months of his high school career.

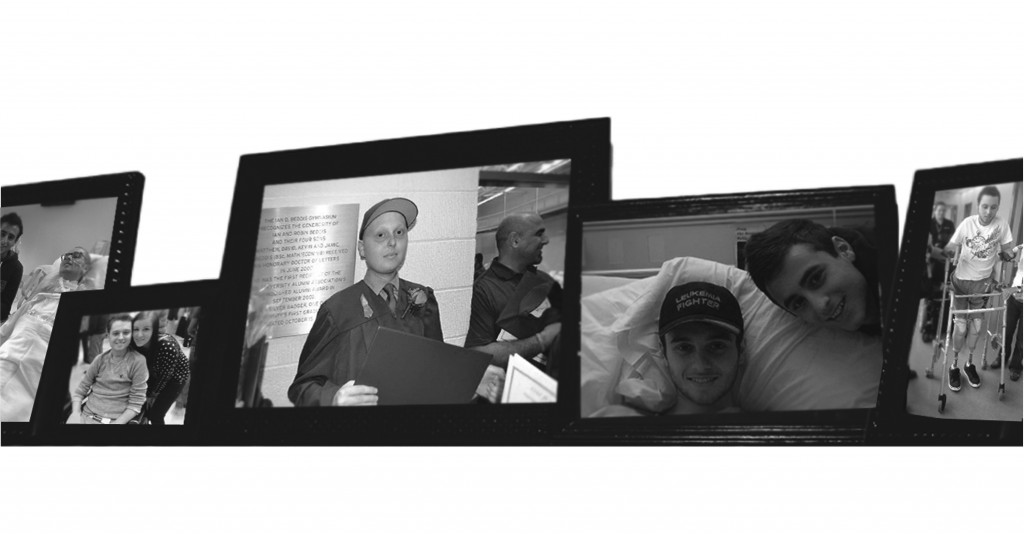

Nick was able to attend prom with his girlfriend of over three and a half years, Brown, where the two were named prom king and queen. Just three weeks later, and six months after being diagnosed, Nick walked across the stage at his graduation with no help, an orange ribbon on his graduation robe for leukemia awareness, and received a standing ovation from his classmates and parents at Saint Paul.

“It made me feel like I can accomplish anything no matter what the obstacle is,” Nick said. “It was a big thing for me.”

“To see him walk across the stage at grad meant so much to me,” Brown echoed. “I was so proud to be there and witness everyone giving him a standing ovation. I was so happy he was able to attend prom with me and we were able to put everything aside for a moment and just have fun.”

The summer

Despite Nick’s progress, things took a turn in July 2012. While Karen was in Croatia with her fiancé to see his father, who was having open-heart surgery, Nick suffered a blood clot in his leg. He was taken to GNGH, but as the day went on, the prognosis got worse. Nick went through a serious infection and severe septic shock. He was transferred to McMaster to be taken care of by the same doctors that helped him seven months earlier.

“The news got really grim,” Karen said. “I got a message from my ex-husband saying get here quick. We called the hospital … but they wouldn’t tell me much.

When I finally got to McMaster, I couldn’t believe what I saw. I couldn’t believe that this was my child, lying there on life support. It was hell for me.”

Nick had died three times — once in his father’s arms — and had to be resuscitated every time. Originally, he weighed 160 lbs., but because his organs were shutting down, he had to be pumped full of fluids, weighing in at 190 lbs. His fingers and toes were black. He slipped into a coma for six weeks.

“I didn’t even recognize him,” Karen said.

The doctors at McMaster did everything possible to mend Nick’s hands and feet, which were now losing full circulation and were beginning to die. The infection caused blood clots throughout his body, in his leg, lung, heart and brain. He had his first stroke. He had a fever of over 40 degrees due to the infection.

“When we give chemotherapy, it knocks out all of the cells that are dividing, which include the good cells in the bone marrow,” Portwine explained. “So not only will the leukemia cause the number of good cells to be lower, but the chemotherapy provided will [also] certainly bring the number of good cells down. So anybody receiving chemotherapy will be at risk of infection.

“So it’s all part of what Nick went through when he got his infection. It wasn’t just the leukemia that gave him [the infection], but it was also the chemotherapy that we gave him because that brings his counts down and makes him more susceptible to infection.”

The infection forced Nick and his family to make a tough decision. His hands and feet were too far-gone and if the doctors didn’t amputate them, they would amputate themselves. Before that would happen, the infection would kill him.

“I knew it,” Karen said. “But I wasn’t prepared when they said they’d have to come up just below the elbow and just below the knee.”

Karen explained that the logic came down to “life over limb.” If the doctors didn’t amputate his limbs, Nick would die. Portwine was one of the doctors in on the discussion, along with the intensive care doctors, the orthopedic surgeons, the infectious disease doctors and the plastic surgeons.

“When you have an infection that is festering in a limb that you can’t get control of, sometimes you have to do something drastic to eliminate the infection,” Portwine said. “His limbs were very badly damaged and were not going to recover and his best chance for overall survival and recovery was to do the amputation.”

The doctors amputated his hands and feet. Everything was successful.

But that wasn’t the end of the complications.

A week after the amputation, the doctors sat Karen down to express their concern about a blood clot in Nick’s head that caused a seven-millimetre aneurysm. The aneurysm, which is a bulge in the artery, has the potential to burst anywhere between seven to 12 months.

“If that bursts, then he will either be paralyzed or it will kill him or make him mentally challenged,” Karen said. “So I said, ‘okay, what are my options?’”

Karen’s options were limited immediately. Because Nick hadn’t received chemotherapy during the infection, the doctors were unsure where the cancer treatment was at and if came back aggressively. So, they had to wait.

Once the doctors had confirmed that Nick’s cancer was still in remission, they waited a month before performing the surgery. But not without complications. The surgery required that a wire go up Nick’s groin, up his arteries, all the way to the brain and coil the aneurysm, pulling it out. There was a 20 per cent chance that he could get worse. He could become paralyzed, or it could possibly kill him.

“It was successful, the only thing was that it gave him another small stroke that affected the left side of his body. But you can never tell,” Karen said.

By the end of the entire procedure, Nick had suffered two strokes, a brain aneurysm, went through septic shock and lost all of his limbs due to infection.

“So when that was done, I was like, ‘okay, is that it?’” Karen, relieved, said, laughing.

Brown echoed Karen. “Honestly words cannot describe how I felt this past summer with everything going on, it is something I would not wish upon anyone. It was a nightmare.”

The recovery

March 21 became one of the Romas favourite days of the year.

Fifteen months after being diagnosed with leukemia and nine months after battling an infection, Nick was discharged from Hamilton General Hospital and walked out on his prosthetic legs.

“Since [the summer], it’s been smooth sailing,” Karen said. “Once they realized his cancer was still in remission, they said, ‘okay, there’s hope.’ And they did everything they could, the doctors were amazing, at Mac and Hamilton General.”

Nick has undergone intensive rehabilitation to learn how to use prosthetic arms and legs to do things normal people take for granted. With the help of his parents, his family, his girlfriend, Brown, and his brother, Jamie, he’s been able to focus on the recovery.

“I have to go to physio twice a day, where I learn how to do things that most people take for granted,” Nick said. “Like walking, holding things, picking things up. It’s all new again.”

“The therapy that Nick is in right now is actual the maintenance part of his therapy, which means he sees us in our clinic once a week for outpatient chemotherapy,” Portwine explained. “He takes pills at home, but he comes once a week for intravenous medication and what we call lumber punctures. Because we want to keep the fluid around his brain and spinal cord free of disease.

“So periodically we give him chemotherapy into the area that surrounds his brain and spinal cord. He doesn’t come to us all that often anymore, it’s really all outpatient therapy unless he runs into a complication he needs admission for.”

“It is honestly amazing,” Brown said of his progress. “It’s crazy to see how far he has come from where he was back in July, seeing him and his smile each time I go up to see him [in Hamilton] just reminds me of how something bad can turn into something so good, he is such a strong person.”

The initial estimated cost of Nick’s prosthetic legs and the revamping of his Niagara-based homes to accommodate his needs was $500,000.

According to Karen, so far $230,000 has been raised towards the cost, which is almost halfway to the amount they wanted to raise. The prosthetic arms cost approximately $60,000 each and only last five or six years before they have to be replaced.

While Nick’s journey through his diagnosis has been full of complications, Portwine stressed that not all leukemia patients go through the same experience.

“Nick has been an exceptional patient,” she said. “I don’t want to leave the impression that this is the norm for individuals with ALL. Yes, they can become very sick and I think Nick is an example of how sick they can become, but it isn’t the norm. If you came into our clinic [at McMaster] and saw the kids running around and playing … you wouldn’t even know they had cancer.

“So, I don’t want to leave the impression that all kids get as sick as this, but certainly they can. And Nick’s an example of that.”