Fitting the Olympic mould

They say it takes a village to raise a child. The same thing can be said about athletes.

With the 2014 Winter Olympics in Sochi, Russia recently coming to a close, one can reflect on their favourite sporting event and consider the effort that these athletes have poured into what may be their life’s work. Their dedication towards their sport has helped define who they are.

Before athletes are told to aim for that one “big moment,” there is the process of training, overcoming metaphorical and literal hurdles, as well as the tutelage of coaches.

These are the elements that create strong competitors.

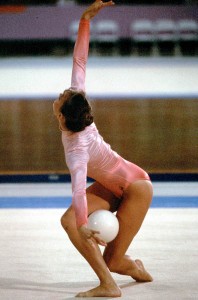

Adrianne Dunnett-Yeates, who represented Canada in the 1984 Olympics in Los Angeles for rhythmic gymnastics, sees her former athletic career as a series of obstacles that she had to overcome. She was 14 when she was referred to a coach who trained Dunnett-Yeates for rhythmic gymnastics. For seven years, she was on the Canadian national team in group competition. Dunnett-Yeates decided in 1981 that she was going to train as an individual for the Olympics.

Two days before the National Championships in October of 1983, where it would be determined who would represent Canada in the Olympics, Dunnett-Yeates broke her foot. Determined even in injury, she showed up.

“I just decided to show up and I went to the National Championships with my foot in the cast, and my coach had our trainer at our gymnasium who made a training plan for me and they sent all of my athletic information to the Olympic committee and said that I was the best choice, even though I had this injury,” Dunnett-Yeates recalled.

“About a week after the National Championships, I got the call and they said ‘yes, they were going to take a chance and they were going to send me.’”

Dunnett-Yeates trained in British Columbia for a month before the Olympics. When she competed in 1984 in Los Angeles for the women’s individual in rhythmic gymnastics, Dunnett-Yeates was ultimately ranked in seventeenth place while fellow Canadian gymnast, Lori Fung, received the gold. Thirty years later, Dunnett-Yeates’ athletic career has been defined by the moments leading up to the Olympics, not just the event itself.

“I look back on my process, my days in the gym and my teammates and my coach, who had such a big impact on my life and who I am now, so when I think back on my career, it’s less about that Olympic moment,” Dunnett-Yeates said.

“The Olympic moment is a marker that marks the real accomplishment that was the everyday in the gym, when you’re tired and you’re hurting and you have to find the strength to go and get better every day.”

Recognizing talent

As it was for Dunnett-Yeates, making the first step toward an athletic career begins with finding the sport you are most passionate about.

When Ryan Bailey began speed skating during high school, he knew it would be a sport that would take him places. Though he was involved in other sports, Bailey had an undeniable talent for speed skating and decided it was the sport he would dedicate himself to.

“I knew that if I wanted to make it big in one sport I had to focus on a specific sport,” he said. “For me, it was speed skating.”

At the age of 16, Bailey moved out to Calgary and rented a basement apartment with financial support from his parents. Bailey trained for three years, with the highlight of his speed skating career occurring when he came second in a Junior World Cup event. He also competed at the Canada Winter Games for Team Ontario.

“You learn from your sport how to be disciplined and apply that to your life.”

Choosing your sacrifices

When it comes to training, an athlete is either all in or all out. There is seldom ever room to settle in-between.

Preparing for that one big break which will define an athlete’s career is a full-time commitment. Kimberly Dawson, a professor in sports and exercise psychology at

Wilfrid Laurier University, explained that the strenuous training process leaves little room for anything else.

“They have to be able to make the sacrifices and adjustments in their lives. That’s why you see a lot of athletes struggle with jobs and going to school,” Dawson explained. “Part of the process is [to] spend an amount of time training so you need to be able to have that time in your life first of all to do that.”

Bailey, who trained four to five hours as a speed skater, found that his love of the sport took precedence over other aspects of his life, including school, finding a job and spending time with friends and family. Bailey believes that between school, work and sports, the most an athlete should do is two.

“If you want to make it in a sport it requires a lot of dedication and motivation, you have to want to do it,” he said.

“There were some years where I didn’t go to school because I was trying to make it in speed skating. You also have to make sacrifices and figure out for yourself what is your main priority. Is it sports? Is it education? Is it your relationship? You have to do what you want to do.”

When she was in high school, Dunnett-Yeates recalled the days when her mother would drive her to practice and she would train for three hours every night and she would then come home eat dinner and then do her homework. Despite this, Dunnett-Yeates does not feel that she made any sacrifices.

“If I sacrificed something, it was maybe what other kids were doing but, to me, it didn’t feel like a sacrifice. It didn’t feel like I was giving up anything that I wanted that I wasn’t getting,” she explained. “I had an unusual youth experience and maybe now upon reflection I gave up extracurricular and being part of that school life, but that wasn’t a priority for me.”

‘A give or take relationship’

While support of an athlete’s family and friends are indeed essential, establishing a healthy and strong relationship with their coaches are a main priority for athletes in training.

The coach can be viewed as the engine in the gym, as they help to create the dynamic and the energy and they help to create the general attitude of the training space.

Making sure that this relationship is functional has a direct impact on the athlete.

Dawson explained that for such a relationship to work, trust must be earned on both sides, as the coach and athlete will be spending all of their time together.

“You need to have a trusting relationship with that individual because you’re going to spend more time with that individual than you’ll spend with anybody else in your life at this juncture so it’s a give or take relationship,” Dawson said.

“You have to be able to trust your coach and follow the workout schedule that they give you and don’t really argue back with your coach,” Bailey added.

When Dunnett-Yeates was preparing for the Olympics in 1984, coaches were not worried about nurturing the self-esteem of their athletes. Dunnett-Yeates recalled her coach throwing cassette tapes at her, yelling and calling her names. She thrived off this.

“I understood that if it mattered this much to her, then she thought I was worth it,” she said. “Her style suited me because I understood and appreciated her effort and her desire to see me do well.”

Dealing with disappointment

Sometimes no matter how hard an athlete trains and prepares, they may not be able to reach their athletic goals. However, an athlete is not defined by their failure. They are defined by how well they rise after they fall.

Dawson explained that athletes are prepared to accept the risk that they may not achieve their goal in their sport and to look for ways that they can mentally prepare to have a comeback. She believes that the range of emotions athletes feel when they do not accomplish their goals can be utilized positively for future endeavours.

“They are going to have their emotional reactions, but some of the athletes are going to be productive and some of them are not, so we train the athletes to know the difference between their first reaction and then how they are going to respond and put that in a much more positive way,” Dawson said. “Disappointment isn’t a bad emotion because it says that they can do better for themselves.”

In his last year in Calgary, Bailey tried to make the Junior National Team and he missed making the team by one spot. Having previously tried making the team the year before, Bailey felt he was not improving as fast as he would have liked and decided to move back to Ontario and switch sports. The decision, though, was one that Bailey grappled with for a long time.

“It took me a while to make a decision, and it wasn’t an easy one. Speed skating gave me a lot of knowledge and experience of just sports in general,” he said.

“At the time I was upset, but I knew that it was time for a change.”

Dunnett-Yeates chose to focus on the process that brought her to the Olympics rather than focus on her result. However, that is not to say that she did not come to the Olympics mentally prepared.

“Although I placed 17th, some people would say that was not a great standing but for me that was a great finish. I made the top 20 at the Olympic Finals and personally, I performed well so I came away with a really good feeling,” Dunnett-Yeates explained.

“I think how [athletes] deal with disappointment is you feel it. You let yourself feel it when it happens, and for the next couple of days after it happens and then you put the suitcase at the side of the road and you walk on because if you try and carry that suitcase with you, you will not make it.”

Nowhere but forward

When one door closes, another one opens.

After a major sporting event has come to an end, athletes will either continue to compete and train in their sports or explore other sports, retire or move on to coach Olympic hopefuls.

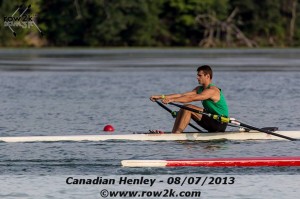

After moving back home and seeing a poster endorsing rowing, Bailey knew that this sport would suit him better, due to his tall height and lengthy limbs. Though they are two different sports, Bailey has been able to apply his work ethic towards his rowing.

“In the long run, [leaving speed skating] ended up helping me because I try to think of the good that came out of my speed skating in Calgary and I just use whatever I’ve learned and try and put it to my training with rowing.”

Bailey is currently attending Fleming College for firefighting. He is hoping to make the U23 national rowing team and the Olympics one day for the same sport.

Feeling like she had done what she wanted to do in her sport, Dunnett-Yeates retired after her experience in the Olympics. The transition was one that she struggled with at the beginning.

“I’m glad I retired when I did, but it is tough to face retirement too,” Dunnett-Yeates shared.

After she retired once the Olympics wrapped up, Dunnett-Yeates went on to coach young athletes at Sports Seneca, an elite training center. She also did commentary for CBC Sports and TSN. Dunnett-Yeates is now married with two grown children. She uses the lessons she’s learned from her athletic career to inspire her children to dream big.

“You can dream big and I have a very positive attitude about dreaming big because my dream came true; I had a dream from childhood that came true, and it came true with a lot of hard work and a lot of effort and its also about knowing where you’re going.”