Evolution of journalism

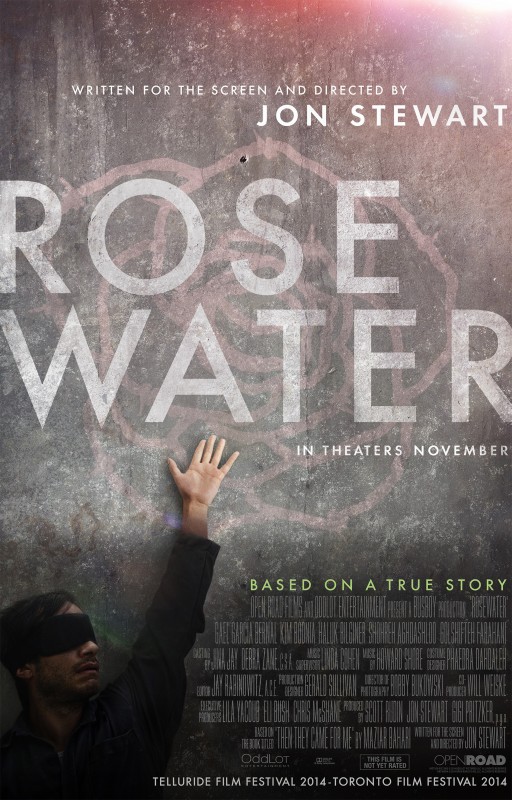

Rosewater unpacks questions about media responsibility

Words are such a simple yet complex thing. On the surface they’re nothing but symbols, but they still possess the power to usurp presidencies and spark revolutions. This is the primary fear of the Iranian interrogators in Jon Stewart’s Rosewater. Their country has suffered so much turbulence in the past that they feel required to put anyone who has even the slightest bit of potential to cause even more in prison.

We have the ability to safely talk about this kind of thing in public, but it calls to mind how many people around the world spread word of political dissatisfaction and spend their whole lives living in fear because of it.

Who is responsible for standing up for these people when they are treated unfairly like Newsweek reporter Maziar Bahari was? When journalists try to enforce a national right to media but are treated with suspicion and distrust by the same government that instated those rights, how can they possibly fight back without negative repercussions?

Director Jon Stewart feels partially responsible for the events of Rosewater, using the film as a sort of atonement. In 2009, Maziar Bahari was arrested under allegations of being an American spy because of an interview he shot for The Daily Show where he and the interviewer facetiously claim to be spies. He then spent four months in solitary confinement with frequent instances of torture inflicted on him, both physical and psychological.

Bahari had the benefit of worldwide attention because of advocacy through the media, but the random faces in the crowd who are suffering the same fate are not so fortunate.

In the film, Bahari talks to a few men who have become advocates for change in Iran because of the Western television they have seen through illegal satellite dishes and near the end of the film it is shown that they are now stuck in prison as well.

These informants — who helped shed light on the public perceptions in Iran — are being persecuted because of it and nobody is coming to help them.

The world is changing and so is journalism. Nowadays the most anonymous person in the crowd has just as much of a chance of capturing something astonishing as the most esteemed photographer.

Think about how the Ferguson incident has caused so much uproar over the police situation in the United States.

Even though townspeople were getting in front of the camera and explaining their dissatisfaction with the system, it did not prevent the police from rashly tear-gassing them in populated residential areas. Does the media owe these peoples personal protection when they are so vital to the process of capturing the story, or is it assumed that these people know the risks and take them for the sake of spreading the truth?

Rosewater seems genuinely concerned with this dilemma, as well as its subjects. While Bahari’s informants are stuck in prison they are not forgotten by him. He wants to give them the help they need, but change does not come immediately. These kinds of informants are becoming more integral to journalism and this film hopes that we get to a point where they are treated as such by those who benefit from them.